Figures like Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Willson Peale, and others were not limited to one profession or field.

They were polymaths—individuals who worked across multiple disciplines, contributing meaningfully to science, politics, art, education, and more.

In their time, the separation between fields was less rigid, allowing them to apply knowledge from one area to another in practical, impactful ways.

Their lives provide clear examples of how a broad, interdisciplinary approach can lead to innovation and societal progress.

Today, with access to vast information and learning tools, we can adopt similar approaches.

What’s needed is the same mindset they embodied: curiosity, adaptability, and a commitment to using knowledge for the public good.

Lives That Spanned Disciplines

Name

Fields

Key Achievements

Benjamin Franklin

Science, Diplomacy, Writing, Invention

Discovered electricity principles, negotiated with France during the Revolution, invented bifocals, founded libraries and universities

Thomas Jefferson

Politics, Architecture, Agriculture, Philosophy, Linguistics

Authored the Declaration of Independence, designed Monticello, spoke multiple languages, and founded the University of Virginia

Charles Willson Peale

Art, Natural History, and Museum Founding

Painted over 1,000 historical portraits, created the first American natural history museum.

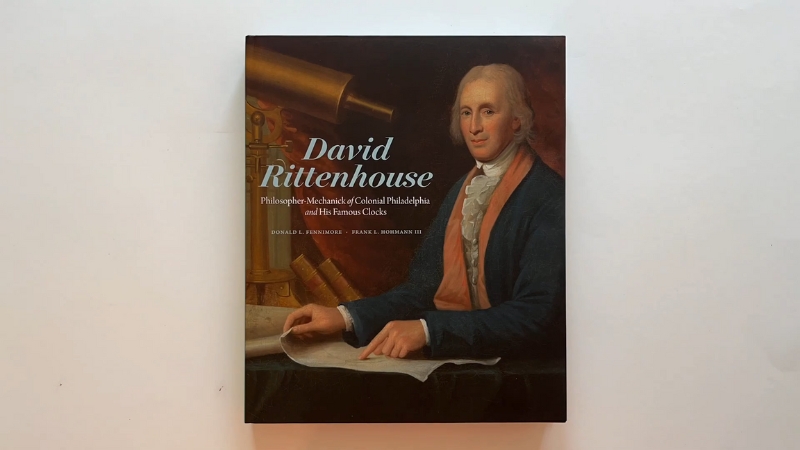

David Rittenhouse

Astronomy, Engineering, Mathematics, Surveying

Built intricate orreries, led boundary surveys, and observed the Transit of Venus

John Bartram

Botany, Exploration, Agriculture

Created America’s first botanical garden, cataloged North American flora, and collaborated with European scientists

Benjamin Franklin

More than just a founding father, Franklin was a relentless experimenter and civic innovator. His kite experiment with electricity is legendary, but his curiosity didn’t stop there—he also invented the lightning rod, bifocal glasses, and an energy-efficient stove.

As a diplomat, he played a crucial role in securing French support during the American Revolution, helping to turn the tide of war.

Equally passionate about the public good, he established America’s first subscription library and helped found the University of Pennsylvania. Franklin’s wide-ranging talents were always put in the service of the community and the country.

Thomas Jefferson

Jefferson is often remembered for his political genius, having authored the Declaration of Independence, but his intellect was vast and deeply interdisciplinary.

He was a self-taught architect who designed his neoclassical estate, Monticello, and crafted the blueprint for the University of Virginia. A passionate linguist, Jefferson reportedly knew six languages and had a deep fascination with classical literature and philosophy.

He was also an agricultural innovator, constantly experimenting with crops and soil management on his plantation.

Charles Willson Peale

View this post on Instagram

Best known for his iconic portraits of Revolutionary leaders, Peale was also a pioneer in natural history. His artistic eye extended beyond canvas to the curation of America’s first natural history museum, where he displayed fossils, taxidermy, and scientific artifacts for public education.

One of his greatest feats was the excavation of a mastodon skeleton, which he assembled and exhibited as a centerpiece of his museum. Peale believed deeply in democratizing knowledge, and his museum was as much a place of wonder as it was of learning.

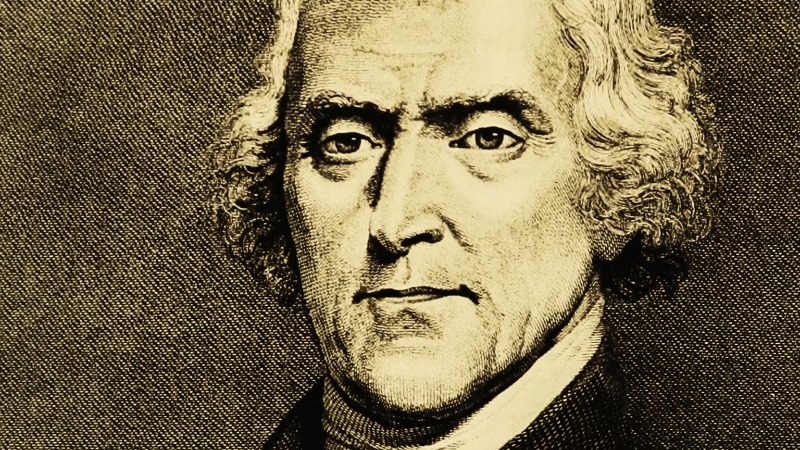

David Rittenhouse

A quiet genius, Rittenhouse excelled in astronomy and engineering despite limited formal education. He constructed highly precise orreries—mechanical models of the solar system—that amazed scientists both in America and Europe.

His observations of the Transit of Venus in 1769 helped refine the calculation of astronomical distances. Beyond his contributions to celestial science, he played a vital role in surveying major territorial boundaries like the Mason-Dixon Line.

John Bartram

Hailing from a Quaker farming background, Bartram turned his passion for botany into a transatlantic scientific enterprise.

He traveled thousands of miles to collect and catalog North American plants, sending specimens to leading European scientists and botanists.

In doing so, he not only enriched global understanding of New World flora but also cemented his reputation as the “father of American botany.”

His home garden, Bartram’s Garden in Philadelphia, became the first botanical garden in the United States and remains a living legacy of his work.

Lessons from Their Lives

1. Curiosity as a Core Value

At the heart of every early American polymath was a burning curiosity. Franklin famously asked, “What good shall I do this day?” and then set out to answer it—sometimes by flying kites into thunderstorms, sometimes by founding civic institutions.

These weren’t men chasing fame or fortune; they were seekers, problem-solvers, learners.

Their example challenges us to ask: What if we treated curiosity not as a distraction from productivity, but as the engine of it?

2. Learning Without Boundaries

Most of these figures had little to no formal education in the fields they came to master. Franklin had only two years of schooling. Peale learned to paint from books. Bartram was a Quaker farmer with a deep love of plants. Their method? Learn by doing.

They read voraciously, experimented obsessively, and weren’t afraid to fail in public. In today’s world of YouTube tutorials and open-source courses, their DIY spirit feels more relevant than ever.

3. Blending Disciplines for Breakthroughs

@mostv98Thomas Jefferson, a founding father and the third President of the United States, left an indelible mark on history through his intellect, vision, and leadership. Born on April 13, 1743, in Virginia, Jefferson was a brilliant thinker, writer, and statesman who played a pivotal role in shaping the United States. Best known as the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson’s eloquent words proclaimed the values of liberty and equality, inspiring countless generations. Beyond his role as a revolutionary thinker, Jefferson was a man of diverse talents—a lawyer, inventor, architect, and avid reader who valued education deeply. His love for knowledge led him to establish the University of Virginia, a testament to his belief in the power of learning. As President, Jefferson orchestrated the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the size of the young nation and opening new frontiers for exploration. He also commissioned the Lewis and Clark expedition, paving the way for westward expansion. Despite his remarkable achievements, Jefferson’s legacy is complex, as he grappled with the contradictions between his ideals and the realities of slavery. This video explores the life and legacy of Thomas Jefferson, a man who dared to dream of a better future and helped lay the foundation of a nation. Watch, learn, and be inspired by his story. Don’t forget to like, comment, and subscribe for more historical insights and fascinating biographies! #ThomasJefferson #FoundingFather #AmericanHistory #HistoryShorts #EducationalContent #USPresidents #DeclarationOfIndependence #InspiringStories #HistoryForKids #VisionaryLeader #USHistory #LearningMadeFun #HistoricalFigures #EducationalShorts #HistoryMatters #KidsLearning♬ original sound – MOS TV

Thomas Jefferson’s interest in classical philosophy shaped his political thought. His knowledge of architecture influenced how he designed democratic spaces. Franklin’s experiments in electricity enhanced his credibility as a statesman abroad.

These are not isolated examples. Throughout history—and particularly in early America—we see how innovation thrives at the intersection of disciplines. Polymaths were (and still are) the ones most likely to connect the dots others don’t see.

4. Knowledge in Service of Society

What makes these polymaths even more remarkable is that their pursuits weren’t purely personal. They didn’t tinker in isolation—they applied what they learned to the world around them.

Their guiding principle was this: knowledge should serve people. In our age of personal branding and specialization, this spirit of civic-minded polymathy is a powerful reminder of what scholarship can be.

The Polymath Today: Can We Still Learn Like This?

Absolutely. If anything, we live in a golden age for polymathy. We have access to more information than Franklin or Jefferson could ever dream of—and tools to experiment, build, and share instantly.

To embrace a modern polymathic mindset:

- Follow your curiosity, even if it seems disconnected from your career.

- Build your curriculum. Blend history with coding, music with physics, art with entrepreneurship.

- Contribute. Share what you learn. Collaborate. Write. Teach. Create.

Conclusion

The polymaths of early America remind us that being many things at once is not a flaw. It’s a strength. Their lives were rich, expansive, and civic-minded.

They weren’t perfect—they had contradictions and limitations—but they were united in their belief that the human mind is vast and capable of more than one calling.

In their world, being a scientist didn’t mean you couldn’t be a statesman. Being a farmer didn’t exclude you from being a philosopher. And being a painter didn’t mean you couldn’t curate a museum or uncover fossils.

Likewise, the contributions of Black inventors, often overlooked, remind us that brilliance thrives beyond boundaries.

That legacy still calls to us.

So the next time you feel pulled toward something new, strange, or outside your lane, lean in. That’s the spirit of Franklin, Jefferson, Peale, and all the others, living on in you.