When we think about great inventors in history, names like Thomas Edison, Alexander Graham Bell, and Benjamin Franklin often come to mind. But what about the unsung innovators whose contributions are just as transformative, yet rarely mentioned in textbooks or classrooms?

Throughout U.S. history, Black inventors have changed the way we live, work, communicate, and stay safe, often while facing immense racial discrimination and systemic exclusion.

These pioneers weren’t just brilliant minds; they were problem-solvers, engineers, scientists, entrepreneurs, and everyday people with extraordinary vision.

Despite barriers like slavery, segregation, and limited access to education, they created inventions that shaped the modern world — from the lightbulb filament to home security systems, refrigerated transport, and even the Super Soaker.

1. Lewis Latimer (1848–1928)

- Key Contribution: Improved Carbon Filament for the Light Bulb

- Also Known For: Drafting patent drawings for Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone

Full Story:

Born to parents who escaped slavery, Lewis Latimer’s life is a powerful story of resilience and brilliance. He started as an office boy at a patent law firm but quickly taught himself mechanical drawing and drafting.

His exceptional talent earned him a promotion to head draftsman. He was hired by Alexander Graham Bell to draw the original patent diagrams for the telephone, just in time to file before Bell’s rivals.

Later, while working for the U.S. Electric Lighting Company (a rival of Edison’s), Latimer invented a carbon filament that drastically increased the life and reliability of the electric light bulb. Before Latimer, bulbs were expensive and burned out quickly.

His improvement made indoor lighting practical and affordable for homes and businesses. He was later invited by Edison himself to join the Edison Pioneers — a rare honor, especially for a Black man in that era.

Latimer also spoke multiple languages, wrote a technical book on electric lighting, and supported civil rights throughout his life.

2. Sarah Boone (1832–1904)

Full Story:

Sarah Boone was born enslaved in North Carolina and later became a free woman in Connecticut. With little formal education but plenty of determination, she worked as a dressmaker — a job that inspired her inventive mind.

The existing ironing boards at the time were flat wooden planks, not well-suited for pressing sleeves or fitted garments. Boone invented a narrow, curved board that allowed users to iron women’s clothing more effectively and with greater precision.

Her design was collapsible and padded — features that became standard in modern ironing boards. Boone’s invention not only eased domestic labor but also elevated the quality of professional dressmaking.

She was one of the first Black women to receive a U.S. patent, making her a pioneer in American innovation, particularly at a time when Black women had almost no voice in science or technology.

3. Granville T. Woods (1856–1910)

Happy Birthday to inventor Granville Woods. Woods was the first Black Mechanical & Electrical Engineer in the US, self taught and held over 60 patents.

He invented and patented Tunnel Construction for the electric railroad system. pic.twitter.com/KFSGk7hMAV

— Ave (@SebastianAvenue) April 23, 2025

Full Story:

Granville Woods was a prolific inventor and electrical genius who held over 60 patents. He left school at age 10 and taught himself engineering and mechanics while working as a fireman and machine operator.

His most revolutionary invention was the induction telegraph, which allowed trains to communicate while in motion. This vastly improved railway safety and efficiency and was a forerunner to wireless communication.

Woods also developed innovations in electric railways, such as the third rail and automatic brakes. These made mass transit systems safer and more reliable — technology still used in subways and trains today.

Edison tried to claim credit for Woods’ telegraph invention and even took him to court — and lost. Twice.

Woods eventually formed his own company, and his work laid the foundation for modern transit systems, telephone communication, and industrial automation.

4. Garrett Morgan (1877–1963)

Full Story:

Born to formerly enslaved parents in Kentucky, Garrett Morgan moved to Ohio and built a life as a tailor and entrepreneur. In 1914, he invented a “safety hood” — a prototype for the modern gas mask — that used a filter and tube to protect against smoke and chemicals.

He tested the device during a tunnel explosion in Cleveland by personally rescuing workers trapped underground.

His second major invention came after witnessing a car accident at an intersection. At the time, traffic signals had only “stop” and “go.” Morgan’s three-way traffic light added a “caution” phase — the yellow light — to prevent accidents, and this design is the basis of what we use today.

Despite facing racism, Morgan successfully sold his inventions and used his wealth to open a Black newspaper and a Black-owned country club. He was an inventor, businessman, and activist, always working toward progress.

5. Madam C.J. Walker (1867–1919)

View this post on Instagram

Full Story:

Born Sarah Breedlove to formerly enslaved parents, Walker was orphaned by age 7 and worked as a washerwoman for $1.50 a day. When she began losing her hair due to scalp conditions, she experimented with homemade remedies and eventually created her own line of hair care products specifically for Black women.

She marketed her products aggressively and built an empire through the “Walker Method” — a system of hair and scalp treatment that included her products and educational training for Black women to become sales agents and beauty professionals.

By 1919, she employed thousands of women and had built a mansion in New York, larger than any other Black-owned home at the time.

Walker used her wealth to fund scholarships, support civil rights causes, and make philanthropy central to her mission. She wasn’t just a businesswoman — she was a movement builder.

6. Frederick McKinley Jones (1893–1961)

Full Story:

An orphan who dropped out of school at 12, Jones was self-taught in mechanics and electronics. He designed one of the first successful refrigeration units for trucks and trains, allowing food, medicine, and blood supplies to be safely transported across long distances.

His invention became a game-changer during WWII, enabling the military to preserve perishable goods and medical supplies in the field. He co-founded Thermo King, which revolutionized logistics for food, agriculture, and healthcare.

Jones also designed sound systems for motion pictures and portable x-ray machines, showing his vast range as an inventor. In 1991, President George H.W. Bush awarded him the National Medal of Technology, the first ever given to a Black American.

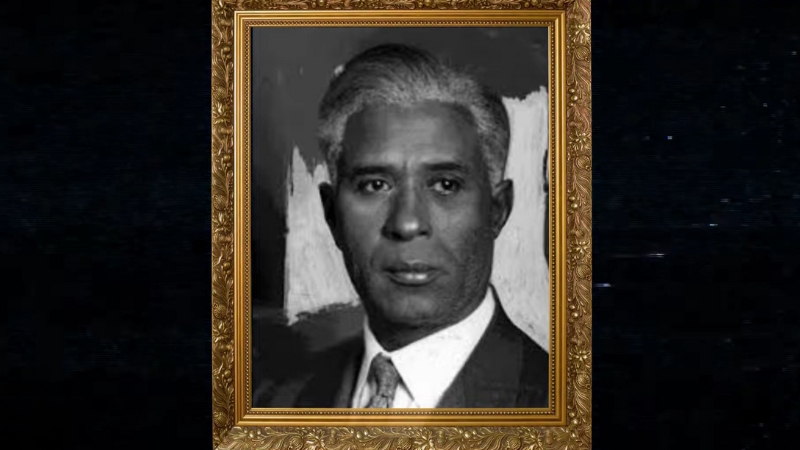

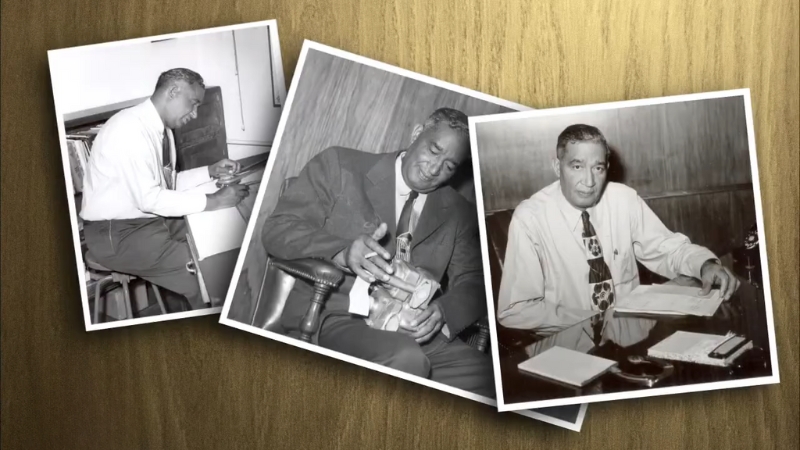

7. Otis Boykin (1920–1982)

- Key Contributions: Resistors for Pacemakers and Electronics

- Other Inventions: Missile guidance systems, burglar-proof safes

Full Story:

Otis Boykin was a master of miniaturization. He developed a precision resistor used in everything from televisions and IBM computers to missile systems and medical devices.

His most impactful work contributed to the development of the pacemaker, a device that helps regulate the human heartbeat.

Boykin’s mother died from heart failure when he was just a boy, which inspired his lifelong mission to improve health technology. Despite limited funding and facing institutional racism, Boykin secured over two dozen patents.

His resistors made electronics cheaper, more durable, and more reliable, contributing to the electronics revolution of the 20th century.

8. Marie Van Brittan Brown (1922–1999)

Full Story:

Living in a high-crime area of Queens, NY, Marie Van Brittan Brown was concerned for her family’s safety. Along with her husband, Albert, she created the first home surveillance system. It included peepholes, a camera that could slide between them, a monitor, and a microphone for two-way communication.

It also had a panic button that called the police instantly.

This invention laid the groundwork for modern-day security systems, including smart doorbells like Ring and surveillance cameras in millions of homes.

At a time when neither Black women nor home tech was taken seriously, Brown’s innovation proved that necessity truly is the mother of invention.

9. Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson (b. 1946)

@yankidudu Shirley Ann Jackson was born in 1946. She is a distinguished African American physicist and the President of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). She was the first African American woman to earn a doctorate in any field from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the second African American woman in the U.S. to earn a doctorate in physics. She was born in Washington, D.C., USA. She earned her B.S. in physics in 1968 from MIT. She completed her Ph.D in nuclear physics in 1973. In 1976, Jackson joined the Theoretical Physics Research Department at AT&T Bell Laboratories. Her work focused on the fundamental properties of materials used in the semiconductor industry. She later moved to the Scattering and Low Energy Physics Research Department and then to the Solid State and Quantum Physics Research Department. At Bell Labs, she researched the optical and electronic properties of two-dimensional and quasi-two-dimensional systems. In 1995, President Clinton appointed her as chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). She was the first woman and first African American to hold this position. In 1999, Jackson became the first woman and first African American president of RPI. RPI has since raised over $1 billion in donations and initiated the Rensselaer Plan, which includes significant capital improvements like the $200 million Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center and the East Campus Athletic Village. Jackson received the National Medal of Science in 2014. She has also been inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame and holds 53 honorary doctorate degrees. She also served on President Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology. She is married to Dr. Morris A. Washington, a physics professor at RPI. They have one son. Jackson has made significant contributions to the field of physics, particularly in the study of electronic, optical, and magnetic properties of semiconductor systems. #BlackScientist #InnovativeMind #ScienceTrailblazer #DiverseInnovation #STEMLeader #InnovativeScientist #DiversityInScience #TrailblazingScientist #ScientificInnovation #BlackExcellence #ScientificInnovation #DiverseGenius #STEMTrailblazer #Innovation #Computing #History #Pioneers #blackhistorymatters #inventions #inventor #innovation #engineering #Technology #STEM #Inspiration #techinnovation #InnovativeMind #PioneeringResearch #EmpoweredScientist #BreakingBarriers #FutureLeader #InspiringChange #InnovativeResearcher #BlackInnovation #SciencePioneer #pioneerwoman ♬ original sound – yankidudu

Full Story:

Dr. Jackson is a living legend. After becoming the first Black woman to earn a doctorate in theoretical physics from MIT, she joined AT&T Bell Labs, where her research paved the way for the invention of caller ID, call waiting, portable fax machines, and fiber optic cables.

Beyond the lab, she became a leading force in science policy — appointed by President Clinton to head the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and later becoming president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Dr. Jackson’s work has reshaped the way people communicate globally, and her leadership has opened doors for countless women and people of color in STEM.

10. Lonnie G. Johnson (b. 1949)

View this post on Instagram

Full Story:

Lonnie Johnson is the rare inventor who is both a childhood hero and a scientific powerhouse. While working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, Johnson was developing ideas for efficient heat pumps when he accidentally created a high-powered water propulsion device, which became the Super Soaker, one of the most popular toys of all time.

But Johnson didn’t stop there. He used the money from the Super Soaker’s success to fund his own research into sustainable energy, creating a solid-state battery and a thermoelectric generator that could change the future of clean power.

He holds over 100 patents and continues to work toward energy independence and STEM education for underserved communities.

Conclusion

The ten inventors featured in this article are far more than names attached to patents — they are innovators who transformed history. Their creations live on in every traffic signal, refrigerator truck, home security camera, and digital call feature.

Among these pioneers was Benjamin Banneker, whose remarkable work in surveying and astronomy helped shape the nation’s early infrastructure, proving that brilliance can flourish even against the odds.

They built empires, saved lives, and opened doors for future generations — all while navigating a society that too often denied them basic recognition.

These contributions challenge the limited narrative of American innovation and serve as a reminder that brilliance knows no race, and invention thrives even in the most unequal conditions.

By learning, teaching, and honoring their legacies, we not only fill the gaps in our historical knowledge, we also inspire a more inclusive future where every mind is free to create.